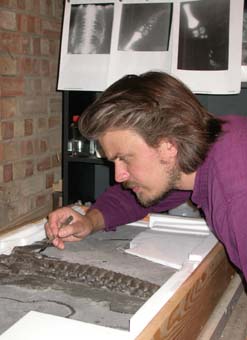

Preparing and conserving an important six-foot long Plesiosaur skeleton for Somerset Museum

A significant project that Nigel has recently worked on for Somerset Museum in Taunton is the conservation and preparation of a scientifically important

plesiosaur skeleton found in Bridgwater Bay on the coast of Somerset. This fossil marine reptile -

from the age of the dinosaurs about 185 million years ago - is six feet long and thought to be the most complete plesiosaur specimen

found in the UK for over a hundred years. In addition, the experts who are

now undertaking research on this skeleton -

Mark Evans (Leicester Museum) and Richard Forrest (of

www.plesiosaur.com) -

think that it might well be the skeleton of a juvenile, making it even rarer -

and possibly even a new species.

Nigel is no stranger to working on fossilised marine reptiles. When working at The Natural History Museum in London he

spent three years working specifically on a project conserving and redisplaying the museum's

world-famous collection of ichthyosaurs,

pliosaurs, mosasaurs and plesiosaurs.

Nigel is no stranger to working on fossilised marine reptiles. When working at The Natural History Museum in London he

spent three years working specifically on a project conserving and redisplaying the museum's

world-famous collection of ichthyosaurs,

pliosaurs, mosasaurs and plesiosaurs.

However, the specialists wanting to study this new important specimen did not have their

curiosity satisfied overnight. The skeleton was encased in thin, hard, brittle sheets

of fossilised seabed mud and it took many months of painstaking labour to free the bones of the animal. The general size and shape of the animal could already be seen when it was discovered, but the actual bones needed to be uncovered for the specialists to undertake their research.

This project has now been written-up and published:

The virtual and physical preparation of the Collard plesiosaur from Bridgwater Bay, Somerset, UK.

By Nigel Larkin, Sonia O'Connor and Dennis Parsons. 2010. The Geological Curator 9 (3): 107 - 116.

For a shorter account, here is the interim report

As the next job was to remove the underburden from each of the blocks to make

them lighter and therefore less prone to mishandling and subsequent damage, the specimens had to be turned over. To ensure the least risk of damage during this process, silicone Wacker rubber (Elastosil-M, the same used in the Palaeontology Conservation Unit at the Natural History Museum in London) was applied to the top surfaces of each block after a protective layer of thick consolidant had set (Paraloid B72 at 25% in acetone, weight:volume) and after water-soluble putty had been applied to the vertical cracks in the sediment so that no rubber would penetrate into the specimen. Jesmonite acrylic resin and glass fibre cloth was then applied to the upper surface of the rubber to provide a rigid support to the protective rubber jacket (one gelcoat followed by three layers of resin and glass fibre each separated by a gelcoat). Once this resin had set, the block was turned over very carefully to lay on this comfortable and perfectly shaped rubber and acrylic resin jacket. These rubber jackets have also taken a perfect mould of the shape of the specimen as found, a record of what the outline of the skeleton looked like enclosed by the layers of sediment. A cast of this, and subsequent replicas, can be reproduced from these moulds if need be at a later date.

As the next job was to remove the underburden from each of the blocks to make

them lighter and therefore less prone to mishandling and subsequent damage, the specimens had to be turned over. To ensure the least risk of damage during this process, silicone Wacker rubber (Elastosil-M, the same used in the Palaeontology Conservation Unit at the Natural History Museum in London) was applied to the top surfaces of each block after a protective layer of thick consolidant had set (Paraloid B72 at 25% in acetone, weight:volume) and after water-soluble putty had been applied to the vertical cracks in the sediment so that no rubber would penetrate into the specimen. Jesmonite acrylic resin and glass fibre cloth was then applied to the upper surface of the rubber to provide a rigid support to the protective rubber jacket (one gelcoat followed by three layers of resin and glass fibre each separated by a gelcoat). Once this resin had set, the block was turned over very carefully to lay on this comfortable and perfectly shaped rubber and acrylic resin jacket. These rubber jackets have also taken a perfect mould of the shape of the specimen as found, a record of what the outline of the skeleton looked like enclosed by the layers of sediment. A cast of this, and subsequent replicas, can be reproduced from these moulds if need be at a later date.

Once each block was turned over, the underburden had to be removed. In most cases, there was a very obvious point at which the block should be split as a very large ammonite had been preserved about halfway through the sediment and provided a major point of weakness in the blocks horizontally. Thin sculpting blades were inserted to encourage the remaining area to be separated, and the freed block of sediment was simply lifted away.

The sections of the large ammonite on the underburdens were consolidated where necessary and all the underburden was kept for future research and display purposes. The ammonite material was quite fragile, and had been preserved as a very thin specimen having undergone considerable compaction. Impressions of the ammonite remain on the undersides of the main specimen blocks. Wooden boxes lined with inert archival Plastazote foam were made for the blocks of underburden to be stored and transported in.

Once each block was turned over, the underburden had to be removed. In most cases, there was a very obvious point at which the block should be split as a very large ammonite had been preserved about halfway through the sediment and provided a major point of weakness in the blocks horizontally. Thin sculpting blades were inserted to encourage the remaining area to be separated, and the freed block of sediment was simply lifted away.

The sections of the large ammonite on the underburdens were consolidated where necessary and all the underburden was kept for future research and display purposes. The ammonite material was quite fragile, and had been preserved as a very thin specimen having undergone considerable compaction. Impressions of the ammonite remain on the undersides of the main specimen blocks. Wooden boxes lined with inert archival Plastazote foam were made for the blocks of underburden to be stored and transported in.

Before preparation commenced, experiments were undertaken with some of the underburden of the small tail block. This was to ascertain which tools to use and whether consolidants could be employed and if so at what consistencies. All but the thickest consolidants were found to make the individual layers of sediment swell and split apart, achieving the opposite effect of that desired. Even the thickest consolidants caused this to an extent and could only be used for areas of sediment that were to be removed later on. Using a scalpel blade to tease the layers of sediment away from one another proved to be more effective (and gentler) than mechanical preparation using airabrasives and percussion tools.

Before preparation commenced, experiments were undertaken with some of the underburden of the small tail block. This was to ascertain which tools to use and whether consolidants could be employed and if so at what consistencies. All but the thickest consolidants were found to make the individual layers of sediment swell and split apart, achieving the opposite effect of that desired. Even the thickest consolidants caused this to an extent and could only be used for areas of sediment that were to be removed later on. Using a scalpel blade to tease the layers of sediment away from one another proved to be more effective (and gentler) than mechanical preparation using airabrasives and percussion tools.

Each of the blocks was tackled in turn with a succession of fresh scalpel blades, teasing the layers of sediment off one another to find the bones within. Body outlines and gut contents etc were looked out for, but none observed. The preservation of the bone surfaces varied, and it was noted that some of the bones of the paddles were extremely porous and friable, with no decent surface, whereas other limb bones exhibited fine surfaces in the middles portions but were particularly poorly preserved at their proximal and distal edges.

Each of the blocks was tackled in turn with a succession of fresh scalpel blades, teasing the layers of sediment off one another to find the bones within. Body outlines and gut contents etc were looked out for, but none observed. The preservation of the bone surfaces varied, and it was noted that some of the bones of the paddles were extremely porous and friable, with no decent surface, whereas other limb bones exhibited fine surfaces in the middles portions but were particularly poorly preserved at their proximal and distal edges.